THE AMERICANS HAVE ARRIVED, but they’re locked out.

In the lobby of the St. David’s Performance Center in Austin, Texas, there’s a bright-green couch and a coffee table and a front desk where an employee sits, back straight and typing. Through the sweeping glass front wall, the desk assistant and I watch a bus pull up outside. After a moment, the players come striding out in that athlete’s walk, the glide in slide sandals both nonchalant and studied. They coast toward the building only to be stiffed at the entrance. A few faces peer sheepishly through the glass, outside looking in. There’s a tug or two on the handle, a push—nothing. The door won’t open.

The staffer scrambles up from behind the desk and hurries over to unlock it.

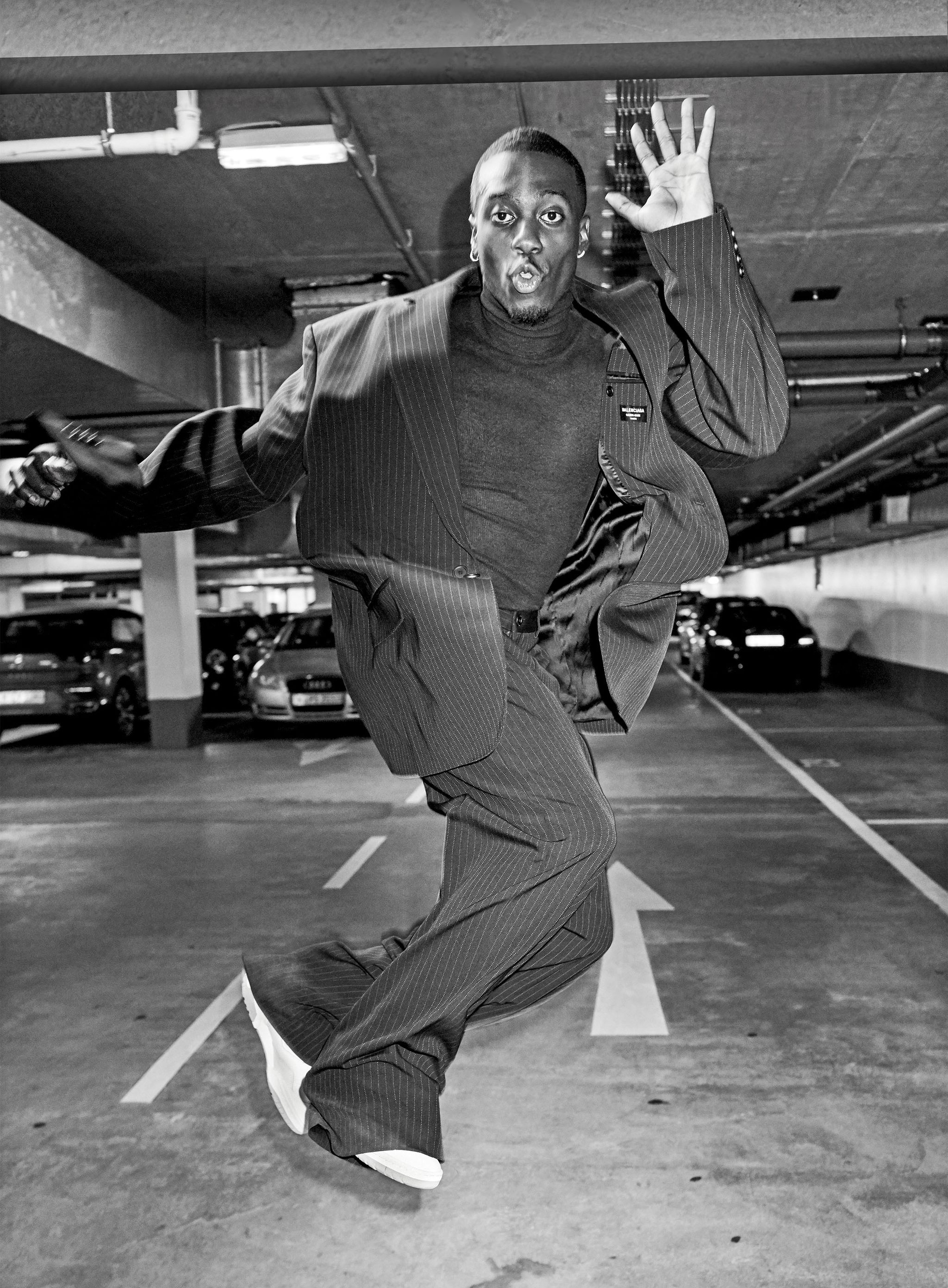

And now here they come, streaming in one after another in a steady line: Aaronson, Adams, Tillman, Wright, Ferreira, Pulisic, Turner, Musah, de la Torre, Robinson, Zimmerman, Arriola, Johnson. As they file past, each offers a quiet “Good morning” almost without fail. Then, from the back of the bus, Tim Weah waltzes in with a boombox bumping some hip-hop. And Weston McKennie, back in his home state, bursts through the glass doors.

“Damn, man!” he booms. “Texas!”

Welcome to the U.S. Men’s National Team training camp. The heat index in early June clears 100 degrees every day here in North Austin, where the players have come together at the practice facility of new MLS outfit Austin FC. It’s a $45 million complex spread across twenty-three acres, with two sets of soccer fields on either side of locker rooms, a gym, medical facilities, a media room, a front office, and a lobby. Coach Gregg Berhalter likes all-in-one setups like this one, and he’s gathered the players here to spend a few days tinkering with tactics and refining passing patterns under the unforgiving Texas sun. After this, the whole team will be together just one more time before the World Cup begins in Qatar in late November.

In Texas, the difference between sun and shade can feel like life and death. But there will be no escaping the heat in Qatar, even with the tournament moved to winter—one of many deeply controversial aspects of FIFA's decision to place the competition there. And there will be no avoiding the hot glare of scrutiny for this U.S. men’s team, the latest in a long line to be handed the daunting task of changing how the world sees American soccer—and how the world’s game is seen here in America. The look of the players bopping through the lobby tells part of the story: mostly fresh-faced twenty-somethings, many barely out of their teens, a few still in them. Almost none of these young men were around last time, when the U.S. suffered the humiliation of failing to even qualify for the 2018 tournament. On average, this is the second-youngest U.S. men’s team to play at a World Cup and among the youngest squads in Qatar. But in more ways than that, they are a generation of American soccer players unlike any who have come before.

WE KNOW, WE KNOW: YOU’VE HEARD THIS STORY BEFORE. You’ve seen the headlines, endured the hype, heard that this is the year soccer becomes America’s game, that our great redeemer has arrived. There was Freddy Adu, the fourteen-year-old phenom who broke into Major League Soccer in 2004 and soon found himself hailed as the American Pelé. Now thirty-three, Adu is clubless, a journeyman who’s spent the better part of two decades drifting from team to team across Europe and the Americas—a cautionary tale of runaway expectations.

And yet every four years at World Cup time, we sing the tune: Is this the year the Americans, forever also-rans, finally break through at the greatest sporting event on the planet? Is this guy—Landon Donovan, Clint Dempsey, now Christian Pulisic—the new star who will ignite soccer’s stateside explosion? The women’s team has already won it all, of course, and more than once. But is this the men’s team that can do the business? And realistically, what does the business even look like?

Whatever success is, it will not be delivered by any American soccer Jesus. Yes, Pulisic has played at a higher level than any American ever, and he’s just twenty-four years old. He wears the fabled number 10 jersey—traditionally reserved for a team’s supreme creative force—at Chelsea in England’s Premier League. But Christian Pulisic cannot save us. That’s up to all of them.

I spent some time in Austin with this team, a mosaic of America whose most crucial components are twenty-four and under. I’ve followed their progress at their professional clubs. And I’ve spoken in particular with a half dozen key players at the heart of this young squad. The story really is different this time. The question is whether different will be enough.

WESTON MCKENNIE TRULY ANNOUNCED HIMSELF IN EUROPE with an outrageous scissor-kick goal for Italian powerhouse Juventus in a Champions League match against Barcelona. Until very recently, this is a sentence that simply would not have been written. Americans scarcely ever played in the Champions League, the highest-level soccer competition in the world—a sort of super-playoff among the top teams in all the European leagues—much less scored highlight-reel goals in it. Landon Donovan, long regarded as the greatest American outfield player, competed in just two matches with little to show for it. Clint Dempsey, in truth a superior player to Donovan, forged a formidable career in the gauntlet of England’s Premier League, but he never played a Champions League match.

But McKennie has, and so have many of his young teammates on the national team. Tyler Adams has played in it with Germany’s RB Leipzig. Giovanni Reyna has with Borussia Dortmund. Tim Weah won France’s Ligue 1 with Lille in 2021, earning the right to play in the Champions League last season. And of course, Christian Pulisic won the Champions League with Chelsea in 2021. He was the first American to score in a Champions League semifinal. With less than a month to go before World Cup kickoff, a single Champions League matchday saw McKennie score a goal, Pulisic create one, and Reyna go to battle against mighty Manchester City.

A version of this article appeared in the Winter 2022/23 issue of Esquire

subscribe

More Americans are playing week in and week out in top-flight European competition than ever before. Yunus Musah plays with Valencia in Spain’s La Liga. Brenden Aaronson, one of the youngest in the bunch, is at storied Leeds United of the Premier League. Antonee Robinson and Tim Ream are also in the Prem at Fulham. In all, seventeen of the twenty-six heading to Qatar ply their trade in Europe’s top leagues.

We are no longer an outfit with a handful of guys trying to make it in the bigs. They’re there. And they will bring their experience playing with and against the world’s very best to every game they play for their country. They don’t have to guess what it’s like playing against Cristiano Ronaldo, one of the four greatest players who ever lived—McKennie shared a locker room with him.

MR. SERIOUS

AT U.S. NATIONAL TEAM TRAINING, a drill sergeant’s call sends the players out onto the pitch, but Weston McKennie can be found a bit off to the side, shooting at a basketball hoop set up on the field’s edge. He squares up for a jumper and promptly airballs. “I didn’t account for the wind!” he says.

McKennie is an eruptive personality, a twenty-four-year-old who speaks for everyone to hear. You get the impression one or two teachers might have sent him to the hallway back in the day, and you still might find him skirting the rules. (In September of last year, Berhalter sent McKennie home from a World Cup qualifier for violating team Covid policy.) Down in Austin, when it comes time for us to sit down for an interview, he opts instead to visit a local Chipotle. In fairness, they sponsor him. And they’ve got queso now.

The coach’s whistle blows while McKennie is still messing around like a high-school gym rat after practice, and he sneaks in one more jumper. No good. “Wow,” he says, making his way over to the huddle. “Basketball’s actually harder than I thought.”

He likes a goof, but do not mistake Weston McKennie for an unserious man. By nineteen, he’d broken into the first team at F.C. Schalke 04, one of the true institutions of the Bundesliga, Germany’s top professional league. By twenty-two, he was starting games in the heart of midfield for Juventus. The kid from Little Elm, Texas—via Washington State and Ramstein Air Base, where his dad was stationed as a serviceman—is the real deal. Catch him in full flow and you will see the very definition of an all-action central midfielder. From box to box, McKennie provides fierce tackling, an eagerness to receive the ball under pressure, clever turns in tight spaces, a decent range of passing, and most of all, powerful running that allows him to carry the ball up the field and past defenders. When he gets an opportunity, he’s also good for a goal.

The next day, as I’m watching the team run pattern drills in Austin that end with one-on-ones against the goalkeeper, McKennie looks to be one of the best finishers in the group. He doesn’t seem in a hurry but arrives at exactly the moment the cross comes in, sweeping it past keeper Sean Johnson with smooth precision.

McKennie and the rest of these young men know the opportunity that lies before them. But just to be sure, when he took over the team in 2018, Coach Berhalter scrawled a new motto on a whiteboard: CHANGE THE WAY THE WORLD VIEWS AMERICAN SOCCER.

The truth, of course, is that the world’s view of American soccer has already changed some. Brian McBride was party to a few of the high-water marks of the American game: his diving header to put the U.S. 3-0 up against Portugal at the World Cup in 2002, his opener later in that competition to send the Americans on the way to their famous “dos-a-cero” victory over Mexico. He was twice voted player of the season for Fulham during his five-year stint in the Premier League. He’s now the general manager for the U.S. Men’s National Team, and I find him on the sidelines, placid in the sunshine as he takes in training. McBride says that when he first got a foothold in Europe, there was still a certain view of American players.

“When I first went over, it was about—there was tenacity, there was a never-give-up attitude,” he says. “That was what they viewed as an American player. But now it’s about the ability to be a game changer. For me, in my position, I needed service. If I didn’t get service, I wasn’t scoring. I wasn’t able to take a game on my shoulders and say, ‘Hey, I’ll break down and create for everybody.’ Whereas we now have a lot of players that have the ability to do that.”

The path to professional soccer has changed stateside. Until recently, the pipeline for soccer talent ran through the college game, where the technical and tactical level was lower and there was more emphasis on physicality. That was reflected in the American style of play and the kind of players we produced. But now more and more Americans are skipping college and heading over to top club academies in Europe at younger ages. As a result, the U.S. has built a cadre of highly skilled technicians with more developed tactical minds. These are young guys who are trained to see and play the game the way kids in countries with far grander soccer traditions do.

“This young team, they play differently,” says Tim Howard, an American goalkeeper who forged a distinguished career in the Premier League. Howard went to Manchester United at twenty-three, then moved to Everton, where he played for ten seasons. He’s now a Premier League analyst for NBC. “There’s a brashness about their youth. A lot of these guys have arrived on the European stage, playing big minutes for big clubs. We can see them bring that back to the national team, that bravado and the swagger and the confidence.”

THE BOX-OFFICE DRAW

GIOVANNI REYNA IS AN ARCHETYPE of the New American player. Reyna grew up in Bedford, New York, but by sixteen he was following Christian Pulisic’s path to the youth academy at Borussia Dortmund, where he quickly rose up the ranks and earned a place in the first team. He made his debut in the Bundesliga at seventeen. Within weeks, he became the youngest goalscorer in German Cup history and found himself playing against the giants of Paris Saint-Germain in the Champions League knockout rounds. Reyna is a fleet-footed trickster with lightning pace who’s box office when he gets on the ball. He takes up positions wide, where he can go right at defenders, beat them, and create something for a teammate. Or he finds holes in the more central channels, pockets of space between the midfield and defensive lines that he can exploit. There he can cut the other team open with a slide-rule pass. At Dortmund, he set up goals for Erling Haaland, the monstrous Norwegian now of Manchester City who at twenty-two is one of the premier strikers in Europe.

Reyna turns twenty just before the tournament, and though he’s over six foot, he has the slight and angular frame of a teenager. He walks into the Austin FC “boardroom” with its wall of windows overlooking the training pitch outside and takes up a place at the head of the table.

“When I first got there, I was in the academy, but I understood the pressure that just came with winning,” he says of Dortmund. You had to win, and you had to be skilled enough, clever enough—not just athletic enough—to play for Dortmund. After years of getting a free role as an attacking midfielder in any American team he played on, he quickly learned that at the top level, he had to be a ferocious front-pressing defender as well. He also learned that in Europe, you get way less time on the ball. One touch, maybe two, then you’ve got to look for a teammate and a combination and a run into space. And he had to learn German. He says he understands it well, especially the soccer talk, but he still doesn’t love speaking it.

It’s an entirely different path from the one that would have taken Reyna through the American college system, the path he thinks his parents initially had in mind for him. Reyna’s mother, Danielle Egan, played for the U.S. women’s team. His father, Claudio, was captain of the men’s team. Both came up through top NCAA programs. Gio has been in Germany for a few years now, and he says he still feels Americans are disrespected in Europe. He mentions “this kind of joke about American players,” but “England or France . . . I think a lot of [those] young guys are very, very overhyped,” he says with some defiance. “Where I see some American kids that are doing the same thing.”

Reyna says it was playing with his older brother, Jack, and his friends that first got him into “real soccer,” got him used to “playing up” with kids older than him. Gio was a natural, a prodigious athlete who could see something on TV and just do it. “It definitely started with that,” he says of playing with Jack in the backyard, which “just gave me my edge and my competitiveness and my fire.” But then, at age eleven, Jack was diagnosed with stage IV glioblastoma—a brain tumor. He fought it, he did nine months of chemo, and it went into remission. But then it came back, and the doctors said there was only so much they could do. Jack died at thirteen years old.

“Everyone has their thing that motivates them a little bit extra,” Gio tells me. “On the days where I don’t want to do my rehab, when it’s already been two months and I still have another two months to go, it’s him.”

THE DEMO MAN

THERE ARE COACHES IN RED U.S.A. SHIRTS milling about on the near training pitch as the sprinklers spritz the far one. Soon the click-clack of cleats on concrete sounds twenty or thirty feet down the way, where a door has opened and the team files out, some lingering locker-room jams filtering behind them. The first ones out group themselves into juggling circles almost instantaneously. “Two to three minutes, then we’re rolling boys!” shouts a coach.

Christian Pulisic emerges on his own, sporting a brand-new bleach-blond dye job. He’s often solo, or beside twenty-nine-year-old center-back fixture Walker Zimmerman—considered an old head in this group—as he stalks around training. Once the players take the field, it’s boisterous—laughing, joking, “Oooouuuuuaaay,” as someone catches that between-the-legs humiliation of a nutmeg in the dribbling drills.

The groups break down after a while and the guys go for water. Tyler Adams is still out on the field, and he rockets the ball at Aaron Long from fifteen feet away. It smacks Long in the calf, and he goes down in mock agony.

“You said you wanted it back hard!”

Soon enough they’re back to work, assembled in formations for a pattern-of-play drill. The ball begins with the center backs, who find a central midfielder who’s come deep to pick the ball up. It goes out wide and then either in to the striker or back to midfield. Then it’s out to a streaking wide forward, who’ll play the ball in for the cast of characters now pouring into the eighteen-yard box. Things sharpen and sharpen until the boys are in full flow, sweeping crosses into the net with thoughtless grace.

“This will be seven in a row!” shouts Berhalter, who stations himself behind the center backs to survey the X’s and O’s and the passes between them, all winding into a network of roots and branches. “This is seven!”

The ball goes out wide again, and in comes a low cross along the ground that keeper Sean Johnson scoops up and sends fizzing away with a one-armed toss.

“Why’d you say it?!” Tyler Adams hollers.

Adams once said he intends to be captain of the U.S. national team someday. Speaking to him, you start to believe it. “When I step on the field, I’m really competitive, kind of like an animal,” he says with the shadow of a grin. The twenty-three-year-old from upstate New York is lanky and hardly towering at five-eight, but he comes directly to the far side of the boardroom, where I’m waiting against the windows. He sits down next to me and opens his body up as he does, a young man in command.

He may not look the demo man of the United States midfield, but he is—the disruptor and the enforcer. Adams sits deep in front of the back line of defenders, breaking up the play, cutting off passing lanes and snapping into tackles whenever he sees a chance. He’s in the engine room of this team alongside McKennie and, increasingly, Musah. Their job is to outwork and outsmart their counterparts in the opposing midfield. Adams wants to win the ball back and set the team on their way up the field quickly. But mostly, he is a testament to the first soccer commandment: Thou shalt earn the right to play. The U.S. team spends a lot of its time up against North American opponents who, outside of Canada and Mexico, usually cannot match them for skill. Aggression and tenacity can be summoned by anyone, though, and the Americans will sometimes find themselves in a bar fight on a bad pitch. In these situations, stepovers and slick passing take a back seat. You’ve got to win the war.

And Adams has seen action. He joined RB Leipzig just before his twentieth birthday, after he debuted with the first team of sister club New York Red Bulls of the MLS at sixteen years old. He started off in the academy in Whippany, New Jersey, and his mom would drive him the three hours round trip from Wappingers Falls, New York, every day for training.

When he arrived at Leipzig, he started all right, but he struggled with injuries for much of 2019 until he got himself in the team just in time for the pandemic shutdown. But when the European season restarted a few months later, Adams was in the conversation still. And that’s when, he says, there came a moment in August when he realized he’d reached a new level: He scored a goal in the eighty-eighth minute of a Champions League match to send the lions of Atlético Madrid packing—and book Leipzig a ticket to the semifinals. An American had made the difference at the very highest level of European competition. I ask Adams whether, when he first walked into that Leipzig locker room, he felt people looked at him as just a footballer, or as a Yank.

“Definitely as an American,” he says. “You always have that sense that you need to have a chip on your shoulder, because coming from a country where soccer is by no means the number-one sport, people view it as a place to come and relax. The ‘retirement league,’ they call MLS. But you just laugh with it and then you show what you can do on the field.”

The question for Adams and his teammates is: What does success look like at the World Cup now? For Adams, it’s simple. The U.S. can no longer play the role of underdogs who are just happy to be there. The task is to go deep enough in the tournament to give teams like Brazil and France a real game. They must approach the competition with a certain degree of arrogance. They must expect more.

At the draw in October, the United States was sorted into Group B alongside Wales, England, and Iran. They’ll play each team once, a round-robin. Three points for a win, one for a draw. That’s the first phase of the tournament, and Team U.S.A. will need to beat either Wales or Iran and take at least a point from the other. That won’t be easy: This will be five-time Champions League winner Gareth Bale’s last dance with Wales, and Iran is a highly organized outfit ranked twentieth in the world. And then there’s England, finalists at the European Championships last year and semifinalists at the World Cup in 2018. That match on November 25—Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving—is a chance for the Americans to show they are no longer at the kids’ table.

If they can weather those three matches and finish in the top two in their group, they’ll make it to the knockout rounds: win or go home, starting with the Round of 16. Progression to the quarterfinals, the last eight, would be a great achievement for a young team with a vision that stretches out to 2026, when the World Cup will be held here in North America. That’s why this team is constructed the way it is: to build a program across this new decade. But they must start to compete, really compete, now.

AMERICAN SOCCER HAS COME A LONG WAY since the 1990s or even the 2000s, but it still isn’t a major sport in this country. TV ratings for Major League Soccer are still lagging, though as of the 2021–22 season, NBC reportedly had an average of about half a million people tuning into their platforms during Premier League matches on Saturdays. Last season, the biggest Premiership games broadcast on the main network—this year, most are on the NBC-owned USA Network or on Peacock, NBC’s streaming service—clocked in at more than a million. But it ain’t football, or even baseball. NFL games averaged 17.1 million viewers during the 2021 regular season, and ESPN’s Sunday Night Baseball games were bringing in 1.7 million viewers at the beginning of last season. So as much as these young players have a chance to change the rest of the world’s perception of the U.S., they also have a chance to change us.

You might have played the game as a kid, as so many Americans do before fixing their devotion elsewhere as fans. You may still remember how it feels to strike the ball purely and flash it past the keeper, hear the cash-register crunch as it hits a tightly wound net. Or, as a defender, to go to ground at just the right moment to hook the ball away and send it up the other end of the pitch.

Soccer is a simple game upon which so much has been layered: tactics and formations and patterns and philosophies, pride and ambition and tribal hatred. But at times, all there is to it is the feeling of taking down your teammate’s raking longball with one deft touch, like a wide receiver reeling in a high pass in the end-zone corner. Or a defense-splitting ball hit with just the right weight, some ideal combination of pace and force to place it perfectly in the path of your teammate’s full-throttle run, the goal at his mercy.

These are the intricacies that make a match enthralling for the soccer obsessive, even when it ends 1-0. These are the fine threads in the fabric of the world’s game. And the hope of American soccer has always been that Americans become fans of the game, not just the jersey. All it might take is our first real run since 2002, when Brian McBride and the Americans exploded into the quarterfinals. Escape the group, overcome the Netherlands or Senegal in the Round of 16, change everything. A breakout like that might tip the balance for a country that’s always greeted the planet’s most beloved sport with the same bemused disdain it harbors for the metric system.

MAN OF THE WORLD

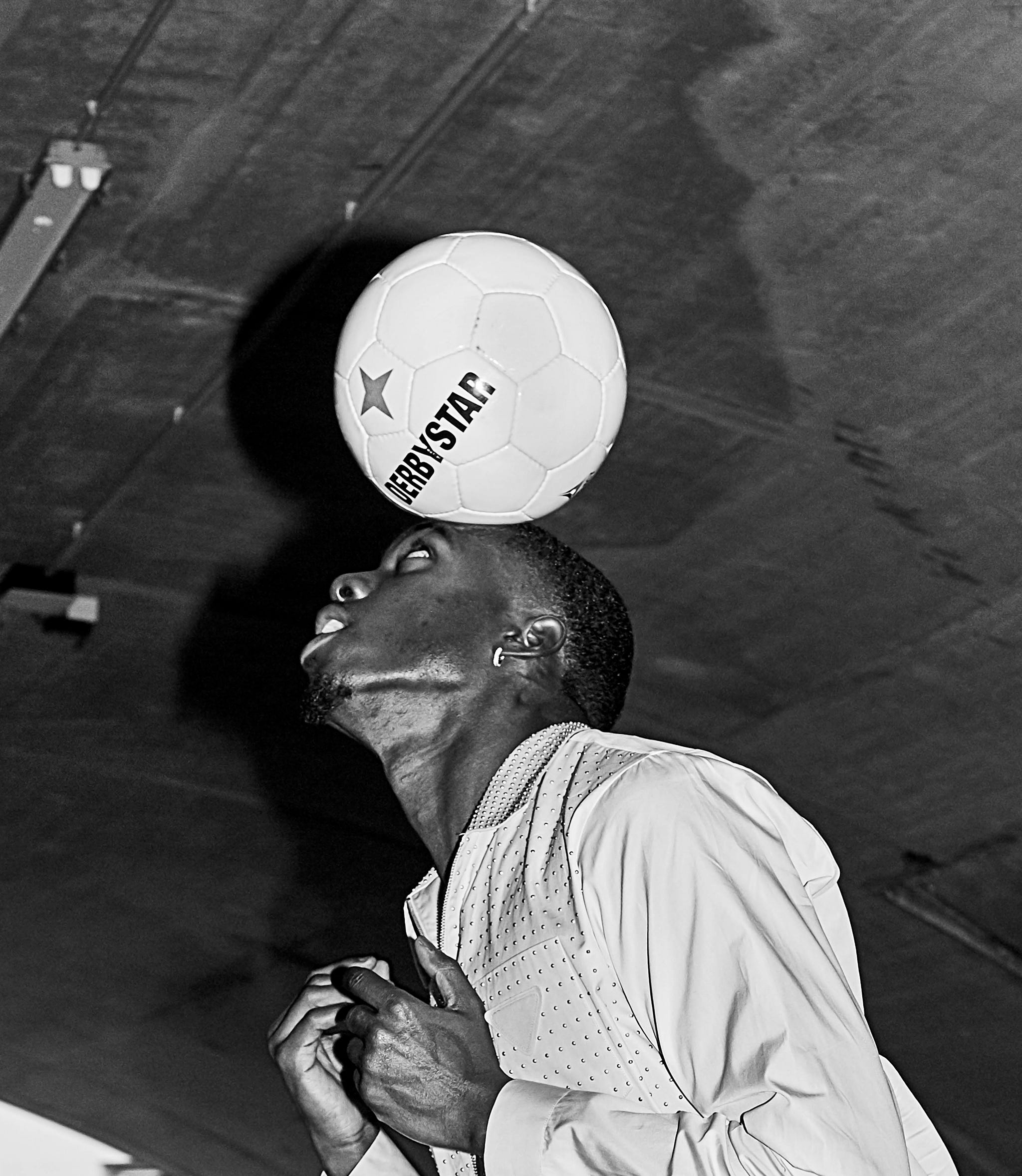

TIM WEAH HAS A PLAN, or at least an approach: He receives the ball on the wing or in the pockets in front of the opponents’ back line, turns, and runs at defenders. If he gets the slightest opening, he will snap a shot on goal. “Once I get an opportunity to shoot,” he says, “I like to just lash at it.” He’s a wide forward in the modern mold, taking up a winger’s positioning with the intent of getting central and scoring. He appears on the far side of the Four Seasons Austin bar, peering around with a hint of curiosity when I spot him. I stick a hand up and he comes over in a smooth, loping gait. He’s in the lobby by himself, no pretensions or public-relations professionals in tow, and nobody at the tables around us seems to notice his arrival. No matter that he represents their country or that his dad was crowned World Player of the Year in 1995. Twice an Italian-league champion with A.C. Milan, George Weah is one of the great African players of all time. Since his election in 2017, he’s had to make do with the title of president of Liberia.

Tim was born in Brooklyn and grew up between New York and Florida. His father’s French citizenship allowed him to go over to Paris Saint-Germain’s academy at fourteen. And his father’s reputation got Tim what he calls “a foot in the door”: trials at Chelsea and Toulouse. The latter is where he says PSG spotted him and offered him a place in their youth program. A few years later, he was in the first team, training with Brazilian maestro Neymar and Kylian Mbappé, the lightning-fast assassin who will power France’s attack in Qatar. Weah learned a lot, but that’s not a forward line you break into, so after a loan at Celtic in Scotland he went to Lille, near the Belgian border, and in his second season won the league at PSG’s expense.

Weah, now twenty-two, isn’t reserved, but he isn’t forward, either. Across the table in the lobby bar, he slouches back in his chair a bit, shoulders sloping, parrying questions like it’s table tennis. While in Paris, he picked up a taste for the big houses of fashion, and he jumps at the chance to get himself into an Esquire photo shoot. Though he was injured for the warmup match in Germany in September, when we photographed the guys, he drove himself over to Cologne from Lille just to make it happen.

He describes himself as having just been “in my corner” at PSG, a part of the group but not at the middle of it. He does his thing. Still, it was Tim who strode off the bus that first morning in Austin with the boombox and an air of absolute assurance. “In a few years, we’re going to be top-class players,” he says as if relating tomorrow’s weather forecast. “And the football that we’re going to play is going to be amazing to watch.”

THE RINGER

BACK ON THE TRAINING FIELD AT ST. DAVID’S, the drills have ended, and five or six guys have set up a dummy wall to practice free kicks. Tyler Adams walks off near the halfway line somewhat gingerly, one knee obscured by a giant ice pack affixed with tape. McKennie catches sight and goes over to chirp Adams, arm around him. Adams pushes him away with a shove on the shoulder blade, and they jaunt over to the sideline with a laugh.

Adams makes his way to the overhang area, where some of us observers are holed up. He chats it up with some folks assembled until they arrive at how one of the team photographers never seems to get angry, even if his shot is blocked out midgame by some wire-service shutterbug. Yunus Musah is walking by and thinks they’re talking about Adams.

“This guy never gets mad?” he says, gesturing at Tyler in complete disbelief.

No, everyone clarifies.

Then Adams gets him back: “Do you ever get mad? When you get fouled, you just yell, ‘Ref!’ and keep running.”

The crowd laughs, and Musah has something of a giggle, too, as he continues on toward the locker room.

Yunus Musah is the latest in a long line of USMNT players who have been recruited to represent the U.S.A. despite not having spent much time living in the States. He was born in New York to Ghanaian parents, but soon they upped sticks and moved to Italy, where he remembers first learning to play the game on the quiet streets of his neighborhood in Veneto, near Venice. When he was nine, they moved again, this time to London. He has the Brit accent to prove it, along with that jovial, sunny disposition of an English lad for whom things are going very well indeed.

He entered the academy at Arsenal, one of the Premier League’s great clubs, and began representing England at youth level. But his family has always approached his career deliberately, strategically, and when Spanish outfit Valencia came calling, promising a faster track to the first team, the Musahs jumped at it. Soon enough, he was playing regularly in La Liga, Spain’s top division, and the U.S. coaches took notice of his progress—and his birthplace. They made a similar offer to the one Valencia had made: a faster track to playing at the World Cup than England could promise. Musah switched his allegiance, started repping the Stars and Stripes. England manager Gareth Southgate only recently stopped voicing his disappointment.

Southgate has reason to be disappointed: Musah is good. Very good. He first got games at Valencia as a winger, but he has since moved more often into central midfield. That’s where he’s also started to get into the U.S. team, alongside McKennie and Adams in what increasingly looks like a three-man setup. Musah is a phenomenal athlete—brawny with pace and power, but with an eye for a pass, too. And like Adams, he has been tested. At Spain’s top level, you find names like Real Madrid and Barcelona on the fixture list four or five times each season. Musah remembers his matchup with Real’s legendary midfield combination of Luka Modric and Toni Kroos with a kind of amused dismay.

“I just couldn’t get close to them. I couldn’t even touch them, because they would just move, pass, move. And at the age they’re at as well, making me run that much—I was the one that was tired. And that was really like, ‘Okay, I’ve got a lot to learn from these guys.’ ”

I ask what he took away from it.

“You realize what makes the opposition suffer,” he says, referring to the quick passing and whirling movement of the midfield machine. “They did things that made me suffer.”

Modric and Kroos will be in Qatar representing Croatia and Germany, respectively. Kroos lifted the World Cup trophy in 2014, and Modric dragged Croatia to the final last time around. That kind of experience can make all the difference when you’re down in the trenches in the seventy-eighth minute of a Round of 16 match, trying to find a way to get over the line. The United States doesn’t have it, outside of DeAndre Yedlin, who came on as a substitute against Belgium in 2014 before Kevin De Bruyne and Romelu Lukaku scored to knock the Americans out in extra time.

But there’s something to be said, too, for beautiful, unburdened naiveté. Most of these men are too young to have experienced the 2018 disaster—only Yedlin, Kellyn Acosta, and a nineteen-year-old Christian Pulisic were on the team when the USA went down 2–1 to Trinidad & Tobago to crash out of qualifying. The clean break that the United States program has attempted to make from its past carries risk, but sometimes not knowing what you don’t know is a liberation.

THE LINK-UP ARTIST

IN THE WOOD-PANELED LOBBY OF THE FOUR SEASONS AUSTIN, I notice Brenden Aaronson talking with a group of players and their families. Aaronson, twenty-two, won the Austrian league for the second time in two seasons with Red Bull Salzburg a month prior. It has just recently been reported that Leeds United paid $28 million to secure his transfer. The vintage English outfit was pulled into a relegation scrap last term, but they survived under the leadership of American head coach Jesse Marsch, who took the job at the end of February and just about saw them over the line. In July, Leeds would reportedly pay $24 million to ensure Tyler Adams joined both of them in northern England. In the Premier League, they’re America’s Team.

Once Aaronson finishes up, I get his attention and he sidles over like a college kid headed to class. Aaronson was never a college kid, of course. From South Jersey outside Philadelphia, he broke into the pros with Bethlehem Steel, the Philadelphia Union’s feeder club, at sixteen years old. He moved up to the Union first team in 2019. He soon caught the attention of Salzburg, who shelled out a fee rising to $9 million for his services.

Aaronson is an attacking midfielder for today’s game, a creator capable of playing across the three positions behind the striker—wide left and right and through the middle. He can receive the ball under pressure in very little space, getting separation from the defender with a deft touch around the corner or by letting the ball run and using his body as a shield. Once he’s turned, he can glide away from that opponent and sometimes one or two more, pulling others out of position so he can lay the ball in the path of a teammate in space. He also has uncanny timing arriving in the box to slot the ball home, often from a low cross that he redirects with one touch below the keeper’s reach.

Aaronson is five-ten but slight of frame, and he has the highly congenial air of someone happy to be here at camp, for whom the novelty has far from worn off. On this day his nose looks to have been victimized by the Texas sun. His hair is a bushel of brown curls, and in another life he might be striding out of the California waves in a wetsuit, surfboard under arm. He’s a kid, really, but one who made it to the Champions League Round of 16 last season with Salzburg before they ran into the buzzsaw of Bayern Munich. That’s what you get playing in the world’s most unforgiving competition, and the kind of experience Aaronson brings to the U.S. team.

I ask him what he saw when he arrived at Salzburg.

“You got to prove yourself. It’s ruthless, but it’s the way it is. They’ll judge you right away. In preseason I felt I had done really, really well, and after three games I started playing week in and week out.”

With Leeds in the Premier League, Aaronson has begun his season shot out of a cannon, thriving amid the kind of intensity he used to find in the Champions League. Every one of the twenty Premiership clubs can punish you for just a second’s lapse in concentration, one mistake. Aaronson had a goal and an assist in his first five games, and has started all of the first fourteen.

“It’s the best league in the world, the physicality, the pace, just the quality,” Aaronson says. “I’ve played in the Champions League, I’ve played against really good opposition, and I’ve done well. And for me, it’s just—now it’s going to be week in, week out.”

JUST BECAUSE AMERICAN PLAYERS HAVE BEGUN to reach the highest levels in Europe doesn’t mean it’s easy to stay there. Fullback Sergiño Dest secured a move to Barcelona in 2020, but on transfer deadline day this year he was sent out on loan because he wasn’t quite making the grade. It’s a very high grade, to be sure, and he’s now with Italian champions A.C. Milan, but going into the partial season of club football before the World Cup, he wasn’t the only American struggling to get on the pitch for the giant clubs who employ them. At Chelsea, Christian Pulisic has fallen down the depth chart on the left wing. Zack Steffen, once the favorite to start in goal for the U.S., lost his place at Manchester City and ultimately in the American World Cup squad. Weah and Reyna have found themselves limited not by talent but by injuries over the last year.

It’s a reminder that, as unprecedented and impressive as these young Americans’ careers have been, they’ve climbed their way up into a mighty arena. At the very top teams in Europe, you are competing against some of the best in the world at your position just to get into the team on Saturday. And Berhalter has been clear that playing regularly for one’s club is key to any player getting a call-up and a place in the starting eleven.

Speaking of Berhalter, his seat is getting very hot indeed. After poor performances against Japan and Saudi Arabia in the final warmup games, the holes at center back and center forward have come into focus. Injuries for Miles Robinson and Chris Richards have created problems in defense, but the problem at striker is something else. Haji Wright and Jesus Ferreira have so far failed to impress at international level, but they’re on the plane. Jordan Pefok, who’s enjoyed a strong start to the season with surprise German-league high-fliers Union Berlin, could not secure himself a call-up to the national team. Neither did nineteen-year-old Ricardo Pepi, who’s thriving in the Netherlands, and at the roster-unveiling event in Brooklyn in early November, Berhalter caught a bit of heckling from the crowd. Some superfans called out Pepi and Pefok by name amid some wider howling. “We want Jesse!” shouted one fan, audibly a few beers deep, referring to Leeds manager Jesse Marsch.

Getting this team ready for Qatar will be a tall order. In midfield, now that Musah has recovered from injury—which kept him out of the September friendlies and our photo shoot—he looks likely to join McKennie and Adams in a very promising engine room. Pulisic is still struggling for minutes at Chelsea, but everything good at the attacking end of things will flow through him and Aaronson and Reyna. Ultimately, this team may live and die by the decisions Berhalter has made, and will make, at center forward and center back. Cameron Carter-Vickers captained Celtic in the Champions League last month. Will he partner with Walker Zimmerman, a Berhalter favorite? Will Fulham’s Tim Ream find his way back in, called up after a long spell out in the cold? And more than anything, the strikers Berhalter’s brought must vindicate him with goals.

The Americans must lean heavily on the attitude that they deserve to be there, that they can give anyone a game. But that doesn’t mean they will always dominate the ball or the territory. Can they keep it compact at the back, limit the shots, and hope for some Tim Howard-against-Belgium performances from the goalkeeper? Can they hit teams on the counterattack with McKennie’s ball-carrying and the lightning pace of Pulisic and Reyna? Can they play strong and smart and true, and eke their way out of the group to face whatever comes in the Round of 16? Can they reach the quarterfinals for the first time in two decades?

The Americans have arrived, but they’ll have to force the door open. Nobody’s going to just let them in, and the only way to stay there—at the top clubs, in the tournament—is to keep barreling forward. If all goes well, DeAndre Yedlin won’t be the only American who’s experienced the ferocity and the finesse of the World Cup knockout rounds when the tournament comes to North America four years from now. There will be a whole team of them entering the prime of their careers and maybe—yes—making football American.

Photographer: Roger Deckker

Stylist: Dan May

Grooming: Nadine Thoma

Contributing Visuals Director: James Morris

Production: Production Berlin

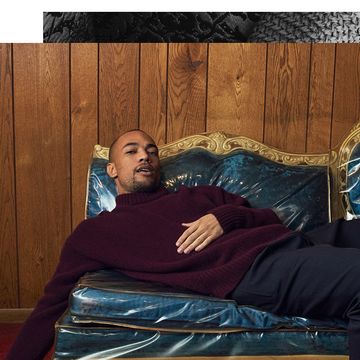

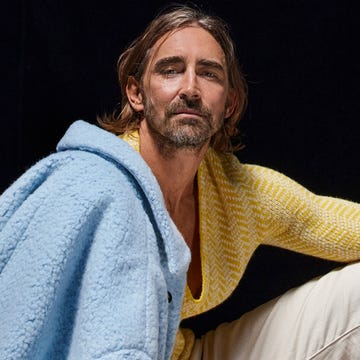

Additional fashion credits: In the opening photo, from left, on Tim Weah: Jacket ($3,250) and trousers ($1,450) by Balenciaga Garde-Robe; turtleneck ($1,590) by Balenciaga; sneakers ($110) by New Balance. On Giovanni Reyna: Jacket ($3,050) and sweatpants ($1,050) by Balenciaga/Adidas; sneakers ($100) by Adidas. On Tyler Adams: Coat by Polo Ralph Lauren; shirt ($765) and trousers ($795) by Rhude; shoes ($1,195) by Giorgio Armani.

Jack Holmes is a senior staff writer at Esquire, where he covers politics and sports. He also hosts Unapocalypse, a show about solutions to the climate crisis.