David Byrne’s American Utopia begins with the sound of birds for close to a minute before revealing the singer, seated alone at a desk, holding a human brain. Otherwise, the stage is empty, save for a curtain composed of hundreds of thin metal chains that line the walls and shimmer like streaks of rain. As in Stop Making Sense, the 1984 Talking Heads concert film, band members emerge as the show progresses. They, like Byrne, are dressed in gray suits, with no shoes, no socks. It’s a stripped-down look for a show that is as cerebral and subtly political as it is raucous and joyful. Byrne wrote or cowrote almost every song in it—a few are from his 2018 album of the same name, and about half are familiar Talking Heads tunes, including a version of “Once in a Lifetime” that’s somehow even more poignant than the original. But it’s a cover of Janelle Monáe’s “Hell You Talmbout,” one of American Utopia’s last songs, that becomes its soul. In between, Byrne muses, philosophically and humorously, on whether babies are smarter than grown-ups and why people are more interesting to look at than, say, a bag of potato chips.

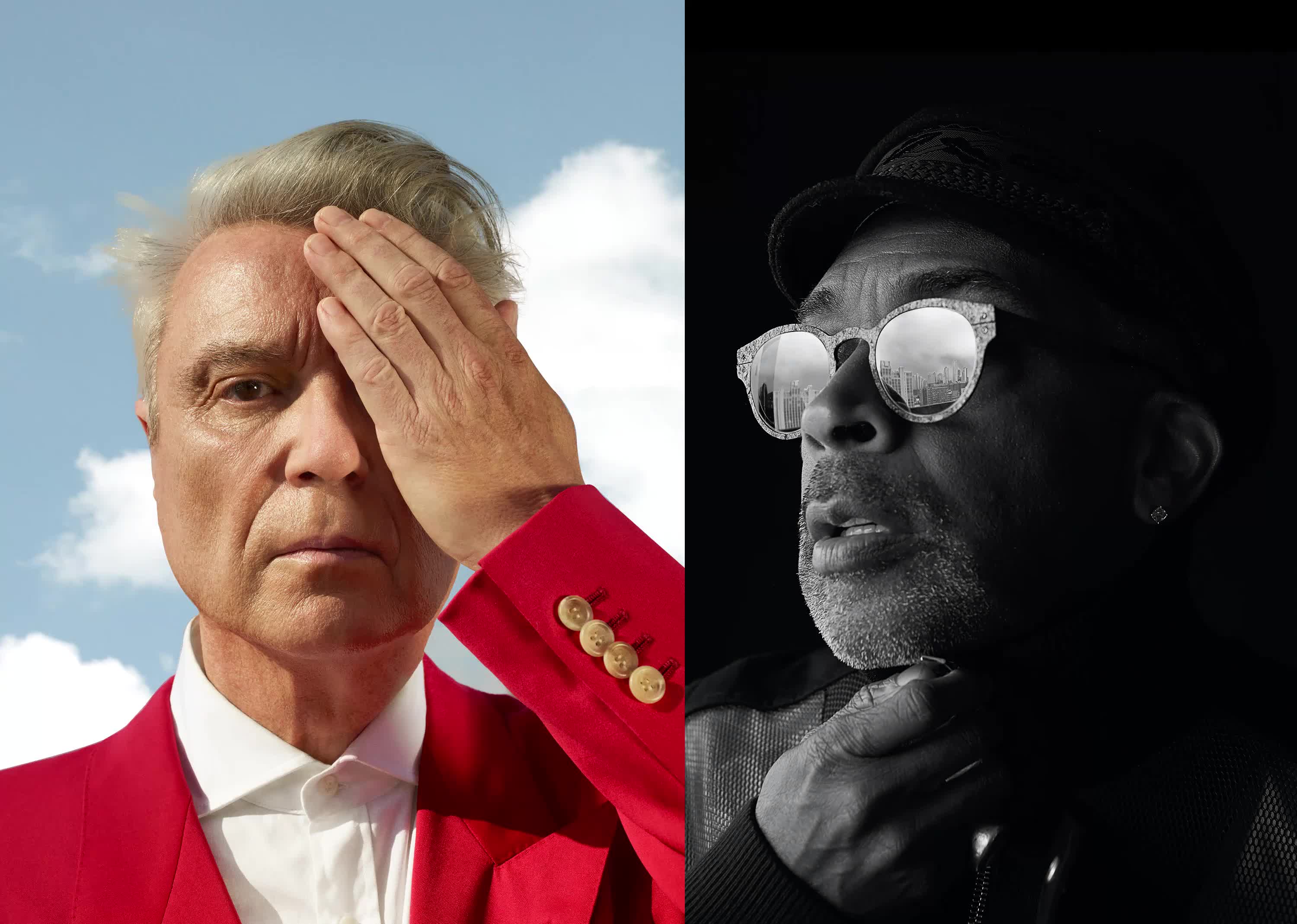

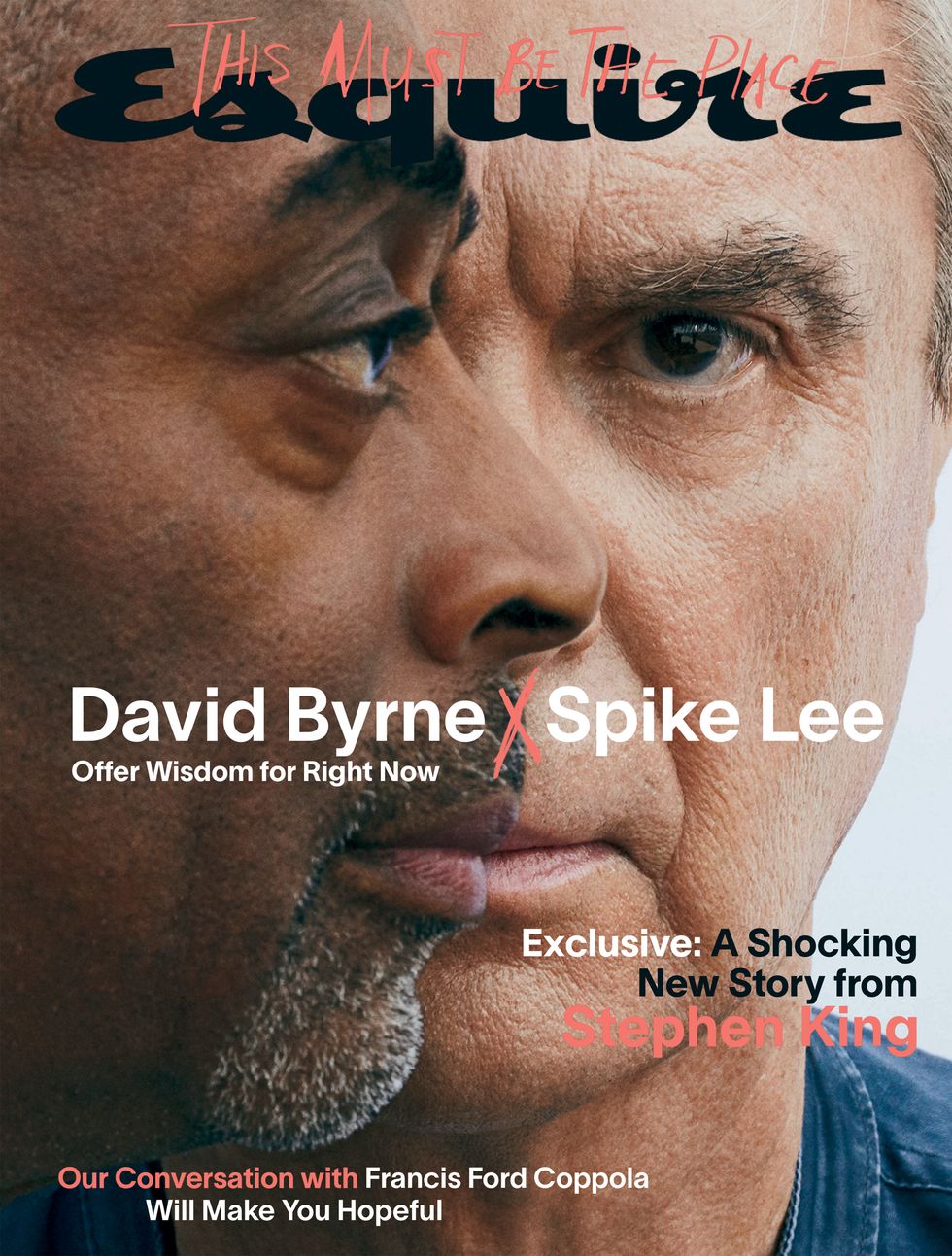

In the summer of 2019, before the start of the show’s run on Broadway, Byrne had the idea to adapt it for the screen. He invited Spike Lee, whom he’d been friendly with for years, to attend previews, then asked whether he’d like to direct. Lee loved the show—and the idea. The result, which comes out on HBO in mid-October, is not a glorified theatrical recording. It’s a real film.

It’s also their first collaboration. Although both made a name for themselves in New York, Lee, who’s sixty-three, came along a few years after Byrne, who’s sixty-eight. The year Lee shot his first short film, 1977, is the same one that Talking Heads, the new-wave band Byrne fronted that made him famous, released their debut LP. (It was called, wait for it . . . 77.) By then, Byrne—handsome, tall like an antenna, and a bit shy—was a regular on downtown New York’s music scene. Andy Warhol was a fan. Talking Heads had premiered live two years earlier, on the beer-soaked stage of CBGB, opening for punk pioneers the Ramones. By the time Lee released his first feature, She’s Gotta Have It, in 1986, the band had banked six albums and six Billboard Hot 100 singles, and Byrne had become the unlikeliest of rock stars.

“Both of us, we have longevity,” Lee says. Sure, he and Byrne have produced their share of clunkers over the years. But that’s the price of the quality that unifies and perhaps defines them: creative evolution. BlacKkKlansman (2018) and Da Five Bloods (2020) are as electric as any other Spike Lee joint. As for Byrne, he collaborated on one of the best concert films of all time (1984’s Stop Making Sense,directed by Jonathan Demme), launched a music label that releases recordings from musicians around the world (Luaka Bop), wrote two books (2009’s Bicycle Diaries and 2012’s How Music Works), and recently started a website. American Utopia, his second musical, was a hit from the start, and it was slated to return in the fall before the pandemic shut off the lights on Broadway. In the final week of its initial run, the show set the theater’s box-office record for weekly earnings—$1.4 million. Consistency isn’t why Byrne is still relevant; it’s his constant transformation. “What I dig about David’s act is: He’s not going to do the same thing twice,” Lee says. “Take a risk and not just do what’s safe.” Right back at you, Spike.

In early September, Esquire spoke with them over Zoom about the film, their personal growth, and life in 2020. Byrne was in his apartment in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, a beer in hand. Lee was at his Martha’s Vineyard home, where a Kehinde Wiley painting adorned the wall behind him.

Spike Lee: David, can you see me?

David Byrne: No, I can’t. All I see is a phone floating in the middle. Maybe if I scroll—there you are. Now I see you.

[Lee holds up a bag of chips to the camera.]

DB: Cape Cod.

SL: Ever have Cape Cod barbecue potato chips?

DB: No, but I’ve had Cape Cod potato chips. They’re pretty good.

SL: I have to do an interview eating potato chips for my brother!

Esquire: Guys, I love the film. I think it will be an awesome gift to people during this time. It fills you with hope. Spike, it felt to me like you have a pretty intimate knowledge of the show. How many times have you seen it?

SL: Well, I first went to Boston, where they were doing previews. Went up on a Saturday morning and saw the matinee, then the night show. Then it was on Broadway. I might’ve went, like, David, five, six times?

DB: Yeah. Five or six times. Spike would come by himself or with family members.

SL: It wasn’t a chore, either. The show is the best! I was doing my homework. I did not know that David had been doing this. I didn’t know nothing.

ESQ: So, David, you had the initial idea to turn this theatrical show into a film, I take it.

This article appears in the October/November 2020 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

DB: Yeah, I had a sense that it had a beginning and a middle and an end and a visual look. So I thought, Let’s see if this could be something that works on a screen. I mean, Spike immediately zeroed in on all that stuff.

SL: It was cinematic!

DB: It’s cinematic.

ESQ: It was!

DB: There’s a character—I mean, it’s me, but it’s also a character who goes on a journey and ends up in a very different place from where he was in the beginning. It’s kind of living inside his head. And by the end, he’s engaging with the whole world. It’s a journey the audience takes as well.

SL: I’m going to cosign what David said. It’s a journey. It’s a narrative. The first time I saw the show, and he’s onstage by himself, I’m like, “Is that a brain?” [Laughs.] Maybe I was not the only person that said, “Is that a brain he’s holding in his hands?”

DB: Spike, I got to ask, at that moment, when the show begins and you just see me sitting

at a desk, holding a brain, were you thinking, Oh, shit, this is not what I wanted to get

into here?

SL: No! Dave, I respect you so much as an artist and as a human being, you know? And so that grabbed me. I had never seen a stage like that. I was hooked.

DB: Oh, good.

SL: I was happy that I was coming back in a couple hours to see the evening show. And I don’t like to spend too much time in Boston, as you see from my hat. [Points to his Yankees cap.]

DB: I remember that after the second show up in Boston, you came into my dressing room and said, “I want to do this. Let’s see if we can get the money.”

SL: Got it done! You see, I’m a big fan. What I dig about David’s act is: He’s not going to do the same thing twice. And I just love artists like that. They’re going to do whatever it is they’re going to do. They’re going to take a risk and not just do what’s safe. Let’s try to explore something. You know, just do it! Love that about David. Both of us, we have longevity in very, very tough industries, music and film. We’re going on four decades. I’m going to tip my cap to the both of us. [Laughs.] I’m sixty-three, you know, David’s the age he is, and we’re still full of energy, vitality.

Tom Byrne was not a musician. He was an electrical engineer and an amateur painter. His wife, Emma, was a schoolteacher and a peace activist. He was Catholic, she was Protestant, and their families did not accept their union. So in 1955, three years after the birth of their first child, David, they left Scotland, where they’d lived their whole lives, for North America—first Canada, then Baltimore.

As a boy, Byrne set about shedding his accent. American kids couldn’t understand him, and he wanted to be understood. But he embraced another element of his heritage: the music. One of his uncles who lived back in Scotland played the fiddle and the mandolin. It was the Scottish folk records his parents listened to that the boy fell in love with. He taught himself the guitar. Then, over a transistor radio, he heard Jimi Hendrix for the first time, and the song’s raw, electric energy was like a revolution. Byrne kept exploring, and the more he learned, the more he wanted to know. Through music, an entirely new world opened up.

ESQ: One of the highlights of American Utopiais the cover of Janelle Monáe’s “Hell You Talmbout,” a protest song in which you recite the names of Black people who have been murdered by the police. In the show, you explain that you asked Monáe if you could cover the song and she gave you her blessing. At what point did the song become part of the show? So much has happened in the past four years.

DB: My band and I were putting a concert together in 2017. I often end my concerts with a cover song. I’ve done Crystal Waters and Whitney Houston and Missy Elliott—

SL: Hold the presses. What Whitney Houston song?

DB: “I Wanna Dance with Somebody.”

SL: “I Wanna Dance with Somebody”?

DB: “I Wanna Dance with Somebody,” the Whitney song.

SL: I would not have expected that.

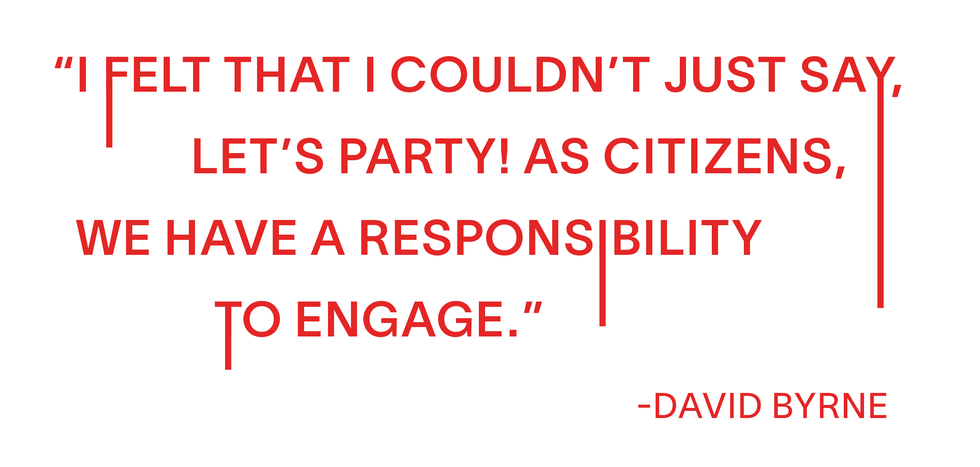

DB: It breaks the fourth wall. “I’m going to step out of character and give you this gift. Let’s have a great time.” But in this case, I thought, Okay, we’re having a great time, but serious things are happening in our country. And I felt that I couldn’t just say, “Let’s party!” As citizens, we have a responsibility to engage. And that’s partly what the show is about: somebody growing into that responsibility and that engagement. I’d heard that song and thought, That’s the one to do. Talked to the band, talked to Janelle, and said, “Okay, we’re going to do this.”

SL: Has she seen it?

DB: No, she’s never seen the show.

SL: We should send her the movie before the HBO premiere. Or at least the song.

ESQ: It reminded me of that moment in Do the Right Thing when Samuel L. Jackson names all of these famous Black artists.

SL: The roll call.

ESQ: The roll call. Yeah. I recently rewatched the movie. Radio Raheem’s death—he’s choked to death by cops—it reminds me so much of what’s happening now.

SL: Like they used to say, “ripped from the headlines.” Here’s the thing about Radio Raheem: I didn’t make that up. That was based on the choke-hold murder of the graffiti artist Michael Stewart. He and Basquiat used to hang out. The New York City Transit Authority police got him in the subway station and choked him out. Then I see Eric Garner—that’s Radio Raheem. Then I see George Floyd, who’s Radio Raheem.

ESQ: Are you surprised that it’s 2020 and this is still the way it is?

SL: Well, I’m going to change hats now. [Takes off his Yankees cap and puts on a hat that reads “1619.”] It’s been like that since we got here. Stolen from Mother Africa. Brought to Jamestown, Virginia, 1619. [Points to the hat.] We were shackled then and, most recently, in Kenosha, Wisconsin, where Jacob Blake, paralyzed from the waist down, was shackled to the hospital bed. And this is 2020.

ESQ: In the film version of American Utopia, you actually see the faces of these Black men and women, and their relatives. Was that your addition, Spike?

SL: Right. You know, I was just listening to the lyrics: “Say their names, say their names.” And there was an opportunity to show their faces, too. But here’s the sad thing. Every time I went to the show, we’d say, “Well, here’s another name that we need to add next week. And here’s another.” After we finished shooting, we added Breonna Taylor, we added George Floyd. Who’s the brother that was jogging in Georgia?

DB: Ahmaud Arbery.

SL: And so now we’ve seen what happened to Jacob—and I really want to talk about this: shot seven times in the back while the officer held on to his T-shirt. His three sons saw him get shot. I mean, that’s horrendous. They’re going to be traumatized for the rest of their lives. I heard Jacob’s father say that he had just come back from the hospital to see his son, whose ankles were shackled to the bed. Where is a man who’s paralyzed from the waist down going to run to? That just showed such a lack of empathy, of humanity. It was animalistic. It seems to me that the police would try to de-escalate, knowing how stuff has been going. But it’s escalating! It’s really a shame that we needed to add more names to that great song. It’s criminal. [Takes a long pause.] David, you speak on that, please.

DB: Oh, absolutely. I loved the song when I first heard it, because it reminds you of the humanity of these people who’ve been murdered. You know, they are not just numbers or something you read in the newspaper. This person had a name. And that takes it out of being some kind of political football. It’s something where you go, “This is not the way we should be with one another.”

SL: That seventeen-year-old kid killed two people in Kenosha with a semiautomatic rifle, shot another person. And after doing that, he walked down the street and armed police vehicles drove right by him. He got to go home. Let me just ask you a question. Let’s switch it, make that individual Black. He’s in the middle of the street with a semiautomatic rifle. Do you think those police vehicles are going to go right by?

ESQ: Nope.

SL: Hell to the no!

“Will you come see my father play?” a young Spike Lee and his brother Chris would say to strangers as they handed out flyers in midtown Manhattan for Bill Lee’s jazz show. “Kid, get out of here” was the usual reply.

Bill Lee was a jazz bassist who’d dabbled in folk, playing for the likes of Bob Dylan; Peter, Paul and Mary; and Gordon Lightfoot. Then Dylan went electric, and everyone wanted electric bass. “Will you play electric bass for us, Bill?” they asked. Nope. Bill Lee was a purist, and he hated the electric bass. His work dried up. Lee’s mother, Jacquelyn, got a job as a teacher at Saint Ann’s, a private school in Brooklyn Heights, to support the family. She was a cinephile, and Bill hated Hollywood movies, so Spike was always her date to the theater. It’s when he first fell in love with film.

While Jacquelyn earned a living and cared for their five children, Bill focused on his art. He was as passionate as ever, but the audiences were not. Sometimes, after his sons had spent all day passing out the flyers, ten people would attend his show. Sometimes even fewer. “This is how I was traumatized,” Lee tells me. “To this day, when I have a movie come out, I hope that someone’s going to show up, and that’s because of my father.” But he says he learned another important lesson. “As I got older, I understood that you must have principles. He was not going to play electric bass.”

ESQ: David, from very early on you incorporated a lot of African polyrhythmic stuff into your music. Were you ever called out for cultural appropriation?

DB: I got accused of that on a record that I did with Brian Eno, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. With that one, we used a lot of found vocals, which—well, a lot of people do it now, but then it was considered wrong. But we went on to doing our music. I mean, we’re all influenced by other things that we see and hear, things people have said or written. We stand on the shoulders of giants. That’s how we make what we do. But yeah, obviously there are lines that are hard to define but that you don’t cross. You’re not just going to steal somebody’s shit and say, “This is mine. I did this.” No. You just stole that shit. But yes, if you can be inspired by something and make it your own, then you’ve created something new. A year or two ago, Angélique Kidjo, a singer from Benin who now lives in Brooklyn, covered the Talking Heads record Remain in Light. But she brought more African influences in than what was originally there. She linked the songs with Yoruba chants and praise songs to the Yoruba gods and things like that. And I just thought, All right, she’s brought it home.

SL: Here’s the thing: The reason why I love David is that he comes from righteousness. It’s not appropriation. Everybody can be influenced by stuff they dig. Now, when I think about appropriation, I think about Pat Boone covering Little Richard’s songs. And he made all the money. I think about Otis Blackwell, who wrote some songs for Elvis and probably got $10,000 and a pork-chop sandwich. So it really depends on the mind-set. It’s like, when you say that you made this, that this is your creation, that’s when you’ve crossed the line.

Dave, you’ve got to talk about Annie-B for a minute. The choreography in this thing is amazing.

DB: Spike and [cinematographer] Ellen Kuras consulted with Annie-B Parson, the choreographer, a lot. They realized that she had created a lot of what you see onstage. She’s great at working with people who were trained in movement, who can remember all these complicated moves, and also with some of the drummers and myself. We can remember some things; our dance vocabulary is limited.

SL: Hold on. David, you are a dancer.

DB: Oh, well, Annie-B likes my dancing.

This article appears in the October/November 2020 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

SL: I like it, too. The point is, you love what you do. So don’t knock your dancing. You’re doing your thing, and people love it. I love it. And the way you dance is your personality. You’re not trying to be Fred Astaire or Gene Kelly.

DB: Yes. I realized I’m never going to be able to do that stuff, but I’ve got to find my own thing.

SL: Yes. That’s what you do, and that’s what makes it great.

ESQ: David, I love that in your book How Music Works, there are a lot of passages about choreography and movement. I feel like everyone else considers you a dancer, but you don’t consider yourself a dancer.

SL: He’s a dancer.

DB: I guess it’s because I’m not trained, didn’t go to school for it.

SL: Hold up. Did you go to school for music?

DB: I’m self-taught in music, too.

SL: You’re contradicting yourself, brother.

DB: Yes. Thank you.

SL: You didn’t go to Juilliard.

DB: No, I went to art school but not for music.

SL: There you go.

In the summer of 1977, after his sophomore year at Morehouse College, Lee was back in New York and unable to find a job. One day, he went to see a friend who’d just received a Super 8 camera, complete with film. “What are you going to do with it?” Lee asked when he saw the box. “You have it,” she said.

Lee spent the rest of that summer shooting with the Super 8. “It was the summer of the blackout. So I filmed my Puerto Rican brothers and sisters and Black brothers and sisters looting,” he says. “It was the first summer of disco. I filmed the block parties, where DJs were hooking up their turntables and speakers to the street lamps.” He edited the footage into his first short film, Last Hustle in Brooklyn.

Around the same time Lee was filming in Brooklyn, across the river, in lower Manhattan, Talking Heads were completing their debut album.

ESQ: On a deeper level, much of your respective work is about questioning the status quo. Do you think that is an artist’s responsibility?

SL: A young Spike Lee would have said yes. I’ve come to realize, in my later years, that everybody’s not the same. Some artists feel that their job is to entertain, to take people’s minds off whatever they’re going through. And I’m cool with that. You know? I’m cool with that.

ESQ: How about you, David?

DB: I agree. If you’re feeling it, you have an obligation to act on what you’re feeling. But it doesn’t have to be directly engaging with specific issues. There are people who, let’s say, just do comedy. They still allow people to see each other in a different way. They’re doing something.

ESQ: One thing I noticed is that both Do the Right Thing and American Utopia end with a callout to vote.

SL: Get David Dinkins in and get Ed Koch out!

ESQ: David, in the show, you mention going down to North Carolina and registering people to vote. What are you sensing out there?

DB: I’m scared about the election. Just the other day, I started reaching out to some voting organizations, because I want to see if it makes sense for me to go to, say, Pennsylvania to get people in a swing state to vote, and to make sure that everybody who wants a mail-in ballot gets one. I think I’ll do it.

ESQ: Spike, how about you?

SL: Well, I’m scared.

ESQ: Yeah?

SL: Because this guy [Trump] is going to do anything to win. It’s going to be skullduggery, shenanigans, subterfuge. And also, I feel that if we don’t come out to vote in the numbers we need for a landslide that’s not in his favor, he’s going to contest the election. I don’t think he’s going to want to leave the White House. This thing is not a lock. I don’t care what the polls say.

ESQ: Spike, when you were doing press for BlacKkKlansman, you said that the 2020 election wasn’t going to be for the president but for the soul of America. And that turned out to be the theme of the Democratic National Convention. You were right.

SL: Right twice a day!

ESQ: Do you think this big movement around racial justice is going to make a dent? Do you think it’s going to continue?

SL: I think so. Because the young generation, not just in the United States but all over the world, took to the streets. They’re still in the streets marching, kneeling, chanting “Black Lives Matter.” And I think that this young generation, they want to be better than their parents, their ancestors. So that’s been very uplifting, to see the support, how this has really spread.

In the mid-seventies, after studying art at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Byrne was offered room and board at a painter’s loft in lower Manhattan in exchange for his help in renovating the place. Byrne’s ambition was to become an artist with gallery representation, solo shows, and the rest of it. His work had a sense of humor, and some of it was outright funny, but nobody seemed to care.

Byrne spent more and more time around the corner from the loft, at a bar called CBGB. Patti Smith and the Ramones were there, too. Inspired by the ideas fomenting before his eyes, there on the dingy stage of the Bowery dive, he, Chris Frantz, and Tina Weymouth—two friends from college—formed a band. A hobby more than anything. Byrne started taking songwriting seriously for the first time, and the band started getting booked at CBGB. They called themselves Talking Heads.

This time, people cared. Talking Heads became an instant favorite among the tight-knit art scene in downtown New York. To Byrne, the immediate affirmative response felt good. If art was a means to express oneself to others, then he’d struck upon his medium. This is working, he thought. I’m going to keep doing this.

ESQ: David, in the show, you talk about how you’ve changed and you still need to change. Were there specific things you were thinking about when you wrote those lines?

DB: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. There was the stuff I’d done in the past, but also more recently. We have to examine what we do and the assumptions we make about others. And that’s an ongoing thing, challenging those assumptions and those biases that are inside us whether we want them to be or not. I may not want to be racist, but if I live in a racist country where there is systemic racism, then it’s inside me whether I want it or not. Part of my life’s work is to try to get it out. It’s like a poison that’s in all of us. So yeah, I’m never done.

ESQ: Do you think you’re a different kind of bandmate now than you were with Talking Heads? It’s my understanding that things could get contentious.

DB: I think I’ve gotten better with that. I think I sometimes failed at that earlier on. I’m not perfect, but I think I’ve learned. Yes, there are kinds of group skills, and management skills, and all those kinds of things. Not that they come out of a book, but I’ve learned to sort of work together with people without yelling at people, by not telling everybody exactly what to do. Letting them have some input, you sometimes end up with something better.

ESQ: You’ve mentioned before that there’s bad blood between you and the other members. Is that still the case?

DB: We’ve reconciled on some things, which is good. Other areas, no, we don’t see eye to eye. For that divorced-couple kind of thing, we actually manage to function okay. It’s not purely cutthroat.

SL: I’m with David. You just got to try to get better every single day. And one of the most important things I ever read, as an artist, was when I was in film school. Akira Kurosawa is one of my favorite filmmakers. In fact, Rashomon is where I got She’s Gotta Have Itfrom. I forget if it was for Ran or one of his later films, but he was doing press in the United States. A writer asked him, and I’m paraphrasing: “You’re one of the greatest filmmakers ever, the master filmmaker. At this stage of your life, you must know everything.” And Kurosawa said, “I see it as an eternity for me to learn.” When he said that, it was like I was struck by lightning. One of my favorite filmmakers in the autumn of his years, saying that there’s still a universe of cinema for him to learn. So that, I mean . . . I don’t want to stop learning until I’ve taken my last breath.

In a 1984 promo video for Stop Making Sense, David Byrne appears as different characters and interviews himself. For one character, he wore blackface, and brownface for another. He’d forgotten about the skit until recently, when a reporter brought it to his attention. Rather than deny it or defend it, Byrne announced the revelation himself. “I acknowledge it was a major mistake in judgment that showed a lack of real understanding,” he wrote in a statement released on Twitter in early September, just days before we spoke. “It’s like looking in a mirror and seeing someone else—you’re not, or were not, the person you thought you were.”

What has been the response? “I’m not checking it all over the place,” he says, “but for the most part, Spike and those on social media have been very supportive.” Though he admits, “There’ve been some places and some institutions that seem to have feelings that maybe I’m a little toxic now. But I thought, This is not about what I did thirty years ago. This is about me opening this up for discussion at this point.And so I definitely stand by my decision to expose myself.”

ESQ: Tell me about the title American Utopia.

DB: A friend suggested it to me. And I thought, Oh my God, people are going to think that I’m being ironic. Or they’re going to think that I’m supporting something that I’m not. And then I realized, No, that is what I’m doing in the songs and onstage. It’s sincere. It’s not ironic. I have to own it. When people see it, they’ll understand.

ESQ: Is the show going to come back?

DB: We hope so. But nobody knows when.

ESQ: Could you ever see that show without yourself in it?

DB: I often ask myself that. Could this go into repertoire?

SL: Nope, that ain’t going to work.

DB: Nah, it ain’t going to work.

SL: There’s no understudy for David. [To Byrne] What’s the title of the show?

DB: American Utopia.

SL: It’s David Byrne’s American Utopia.

ESQ: The show is very hopeful. But if we end up having the same president after November . . .

DB: I knew that’s where you were going.

ESQ: . . . what’s the way forward for the show? Do you change it? Do you tweak it?

DB: I think I would have to. I couldn’t not acknowledge that.

SL: You’d need to write another song.

DB: I might have to.

SL: [Long pause to think the unthinkable.] Nightmares. The world is bananas.